Living in the Santa Ana Mountains, amidst 20 million

southern Californians of the human persuasion, are a few large, tan,

bewhiskered natives of the Golden State — cougars. There aren’t many of

these big cats (also known as the puma or the western mountain lion),

with the California Fish and Wildlife Service giving a very rough estimate of about 5,000 individuals statewide.

The cats who call the Santa Ana range home are facing a severe lack of genetic diversity, according to a recent study in the journal PLOS ONE. Comparing the DNA from 97 pumas in the Santa Ana Mountains with more than 250 from elsewhere in California, researchers from the University of California, Davis, and The Nature Conservancy found that the southern cats were closely related to each other, with a few displaying kinked tails and other signs of inbreeding.

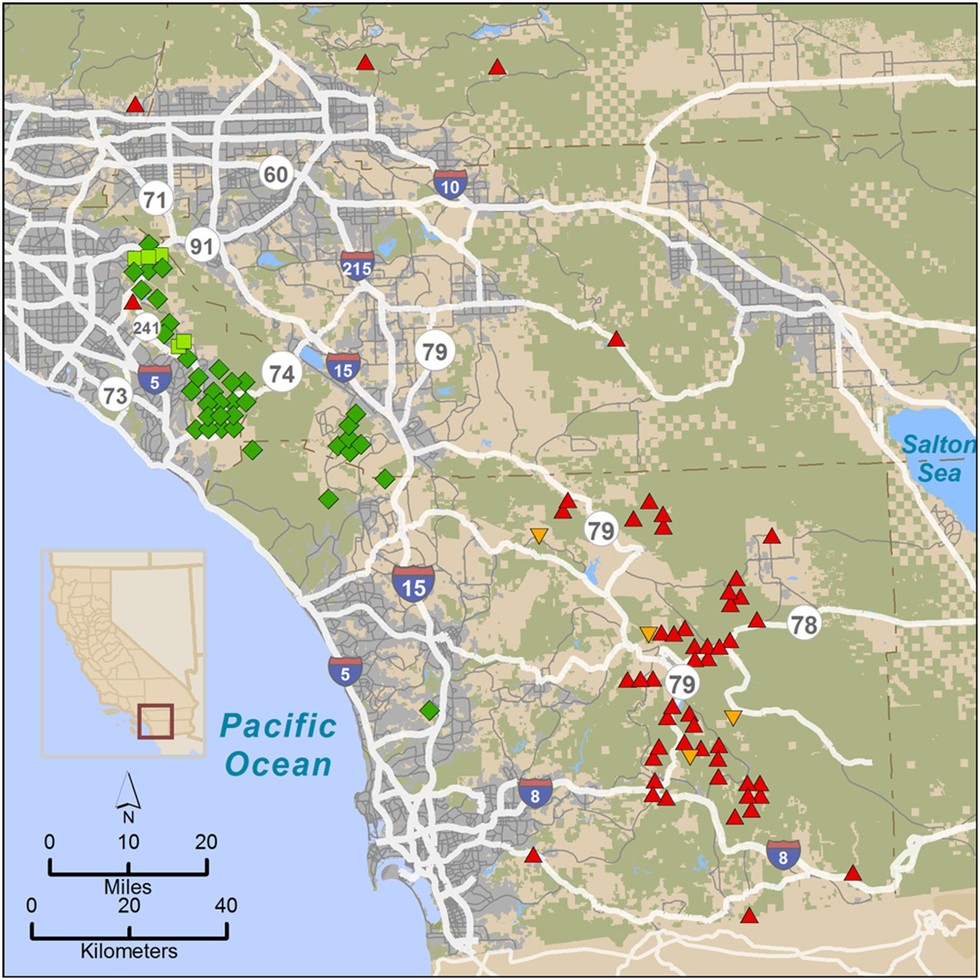

Where this study’s pumas were located, with each color representing a distinct genetic group. (Photo: Ernest et al.)Human development and highways — Interstate 15, in particular — have severed the ties these cougars had with their other California neighbors, the scientists say. "The genetic samples give us a clear indication that there was a genetic bottleneck in the last 80 or so years," says Holly Ernest, a study author and genetic expert at U.C. Davis, in a statement. "That tells us it's not just natural factors causing this loss of genetic diversity. It's us — people — impacting these environments."

Not only do freeways and construction pose risks, but widespread use of chemicals, like rat poison, can also harm California’s pumas.

The good news is state officials are taking note of the way human developments impact wildlife. A proposed $10 million overpass, for example, would connect cougars in the Santa Monica Mountains with those in the San Fernando Valley.

But not all changes would have to be so expensive, according to the authors of this study, like setting aside land as wildlife corridors rather than developing it. "I think there could be hope for this population," Ernest says. "They're at a point where they can be monitored and protected. They don't have to end up like Florida panthers. With early interventions, we wouldn't have to spend millions and millions of dollars later."

source

The cats who call the Santa Ana range home are facing a severe lack of genetic diversity, according to a recent study in the journal PLOS ONE. Comparing the DNA from 97 pumas in the Santa Ana Mountains with more than 250 from elsewhere in California, researchers from the University of California, Davis, and The Nature Conservancy found that the southern cats were closely related to each other, with a few displaying kinked tails and other signs of inbreeding.

Where this study’s pumas were located, with each color representing a distinct genetic group. (Photo: Ernest et al.)Human development and highways — Interstate 15, in particular — have severed the ties these cougars had with their other California neighbors, the scientists say. "The genetic samples give us a clear indication that there was a genetic bottleneck in the last 80 or so years," says Holly Ernest, a study author and genetic expert at U.C. Davis, in a statement. "That tells us it's not just natural factors causing this loss of genetic diversity. It's us — people — impacting these environments."

Not only do freeways and construction pose risks, but widespread use of chemicals, like rat poison, can also harm California’s pumas.

The good news is state officials are taking note of the way human developments impact wildlife. A proposed $10 million overpass, for example, would connect cougars in the Santa Monica Mountains with those in the San Fernando Valley.

But not all changes would have to be so expensive, according to the authors of this study, like setting aside land as wildlife corridors rather than developing it. "I think there could be hope for this population," Ernest says. "They're at a point where they can be monitored and protected. They don't have to end up like Florida panthers. With early interventions, we wouldn't have to spend millions and millions of dollars later."

source

No comments:

Post a Comment