Shannon Kachel, left, the study’s principal investigator, and Ric

Berlinski, Toledo Zoo senior veterinarian, radio-collar at snow leopard

in Kyrgyzstan through a Panthera-supported conservation study.

Shannon Kachel, left, the study’s principal investigator, and Ric

Berlinski, Toledo Zoo senior veterinarian, radio-collar at snow leopard

in Kyrgyzstan through a Panthera-supported conservation study.PANTHERA/RAHIM KULENBEKOV Enlarge

Dr. Ric Berlinski, senior staff veterinarian, recently returned from eastern Kyrgyzstan in central Asia, where he helped trap a wild female snow leopard and fit a GPS collar on her. She was the first ever to be collared in the country, and one of only about 35 to ever be tracked.

“They live in some of the harshest environments you could think of a predator being in,” Mr. Berlinksi said.

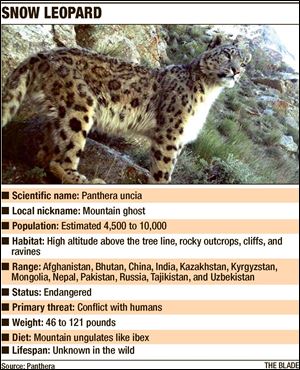

The endangered, solitary cats live at high altitude above the tree line on rocky outcroppings and cliffs. Their superb camouflage and secretive nature make them extremely difficult to find. Many locals have never seen one and refer to them as “mountain ghosts.”

Dr. Berlinski said previously collared snow leopards were humanely snared in areas near human settlements, primarily in Nepal, Afghanistan, and Mongolia. The human-wildlife conflict changes the cats’ behavior, most notably as they hunt readily available domestic sheep and goats.

“The study area we were in is very, very remote,” he said. “We have snow leopards in their natural environment without that human-encroachment factor, so we see a more natural pattern as to what their range is and how they are obtaining their prey. It makes it very, very valuable information.”

Jeff Sailer, executive director at the zoo, said the effort is an example of the zoo’s dedication to preserving wildlife around the world.

“It’s a great opportunity for us. We’ve been known for our international conservation work for decades,” he said. “It helps reinforce our mission, which is conserving wildlife and connecting people with wildlife.”

The veterinarian was invited to be one of three members of the research team sponsored primarily by Panthera, an international conservation group dedicated to big cat species. He traveled to the Sarychat-Ertash State Nature Reserve in the Tien Shan mountains from Oct. 5 to Nov. 5.

The team’s base camp was set in a valley at an elevation of 8,500 feet. Ten humane snares, fitted with transmitters to signal an animal capture, were checked in person daily and monitored from base camp every hour around the clock.

Dr. Berlinski was on duty monitoring the signals at 5 a.m. Oct. 26 when he heard the rapid beep indicating a capture. “My heart rate just took off,” he said. “Of course, she was in the highest snare we had set.”

The team made the arduous hike up to 11,000 feet where the snare had captured a vibrant and healthy female estimated at 6 or 7 years old. Dr. Berlinski was in charge of safely darting her, performing a physical exam and drawing blood, then reversing the anesthetic and watching from a safe distance to ensure she recovered. “I saw her get up and she was still a little wobbly,” he said. “I snuck up again, and peeked over and she was crouched down looking at me. At soon as she saw me, she was gone.”

The veterinarian said locking eyes with the leopard was both thrilling and unnerving. Snow leopards are one of the smaller of the big cats, but also one of the most powerful. “The one description I always give is that they are fluid power, and total defiance,” Dr. Berlinski said.

He noted he gets the same look from the Toledo Zoo’s female snow leopard. “If you’re standing in front of our exhibit and she locks eyes with you, I’ll guarantee you that’s the same feeling I had when I locked eyes with the wild cat,” he said.

The team named the wild cat Appak Suyuu, meaning “true love” in Kyrgyz. In the few days the team had left after collaring her, the group was able to track the cat and determine from footprints she was caring for three cubs. “They’ll have one, maybe two, and out of those two, one will live through the first year of its life,” he said. “For her to have three that were between what we estimated at 16 to 18 months of age based on paw size is incredible. That tells you she is one of the dominant predators in the area.”

The group already knows that she and her cubs have traveled 20 kilometers, or about 12.4 miles, at 14,000 feet in a single 24-hour period.

The collar should last 20 months before falling off. Being able to track Appak Suyuu may allow researchers to recapture her before time runs out and fit her with a new collar to collect additional data.

Despite the difficult conditions and even after experiencing hypothermia, Dr. Berlinski said he would jump at the chance to do it again. “The 40 or so minutes I got to spend with that cat made every second worth it,” he said. “That was one of the most beautiful and remarkable experiences I’ve ever had. I’d do every second of it over again.”

source

No comments:

Post a Comment